An Assessment of DNA Testing for African Refugees |

In March 2008, the Bureau of Population, Migration and Refugees (PRM)—the Department of State agency that processes refugees abroad—halted its family reunification program, known as Priority 3 (P3), because of concerns that there were high levels of fraud in the program. The suspension of the P3 program has had devastating effects on African refugees in the United States seeking to reunite with their relatives. The U.S. accepts disproportionately low numbers of refugees from Africa, and the suspension of the P3 program means that even fewer African refugees have been allowed to enter the U.S. In September of 2010, PRM published proposed rules that would change its procedures for processing P3 applicants, including mandatory DNA testing to prove claimed family relationships. The prospect of mandatory DNA testing is of concern to refugees themselves, refugee resettlement agencies, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and other human rights advocates. Moreover, the implementation of DNA testing in the refugee context may portend required DNA testing in other areas of immigration admissions. Consequently, understanding the particular role DNA testing may play in refugee admissions—its costs, its benefits, and the necessary safeguards if put into use—provides insight into not only refugee admissions, but other issues that come into play in immigration policy, such as how family relationships are proven.

This paper traces the underrepresentation of refugees from Africa in the U.S., the allegations of fraudulent African family reunification applications, DNA testing, and how the U.S. government intends to deal with the issue in the future.

The Development of American Refugee Policy

For over half a century the United States has formally accepted refugees seeking safe haven—reacting initially to the refugee crisis following World War II and gradually expanding its reach to an ever-broader population. In 1980, the United States codified its international treaty obligations and brought its immigration law in line with the refugee definition agreed to by the United Nations, which recognizes a refugee as someone who cannot return to their country of origin because of “persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion” (Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) Section 101(a)(42)). People who have fled their countries and are living in a country of immediate asylum, often in refugee camps, may apply for permanent resettlement to the United States. Processing of applications and admissions to the United States is coordinated between PRM and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in the Department of Homeland Security. Every year, the President—advised by the Department of State and after consultation with Congress—sets a limit on overall refugee admissions, as well as ceilings on admissions from specific regions.

There are three principal components of the U.S. refugee program. Priority One brings in individuals “with compelling persecution needs or those for whom no other durable solution exists,” who are referred by UNHCR or identified by a U.S. embassy or non-governmental organization (NGO). Under Priority Two, members of designated groups facing persecution, often religious or ethnic minorities, are accepted. P2 groups, who are of “special concern” to the United States, are selected by the Department of State with input from USCIS, UNHCR, and NGOs. Under Priority Three, or “P3,” already settled refugees who are 18 or older—called “anchors”—can request that their immediate refugee relatives (parents, spouses, and unmarried children under 21) be considered for refugee admission. The immediate relative is the “primary applicant” on the P3 case and is allowed to include his or her spouse and children under 21, who are the “derivative” beneficiaries. While the primary applicant must establish a refugee claim, the derivatives are joining in the application and do not need to show persecution. The P3 program is only open to those nationality groups designated in the annual Presidential Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions.

African Refugee Admissions in Context

It should be noted that halting the P3 program affected African refugees more than any other group, since 95% of the over 36,000 P3 admissions between 2003 and 2008 were from Africa. Africans have taken advantage of the P3 program in much larger numbers than other groups. This could be due to several factors, including patterns of flight in which families are more often separated, large and extended family networks, and exploitation of the program for outright fraud. Perhaps most importantly, there are large populations of refugees in Africa with protracted histories of exile who have in the past had more limited access to U.S. resettlement than other groups.

U.S. refugee policy historically was part and parcel of the Cold War anti-communist political regime, and as a result privileged those fleeing Eastern Europe, Cuba, and Indochina. European refugees fleeing the aftermath of World War II began to arrive in 1946 under a presidential order and then through Congressional legislation with the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. This policy was followed by the Refugee Relief Act (1953), Refugee-Escapee Act (1957), and the Hungarian Escape Act (1958), all specifically directed at assisting Soviet bloc refugees. In fact, the 1957 Act defined refugees as those fleeing “a communist or communist-dominated countries or the Middle East.” This restricted definition was further codified in the 7th preference of the 1965 Immigration Act. In practice, this anti-communist emphasis meant that, up until the 1970s, almost 80% of the nearly one million refugees who entered the United States were from Europe. The most notable exception to the European-focused policy was the more than 130,000 Cubans who fled after the 1959 communist revolution. With the collapse of Saigon in 1975, Vietnam became the main focus of the refugee program, which—along with Cambodia and Laos—then accounted for the majority of refugees until the mid-1980s. Over a million Southeast Asians came from these three countries under the refugee program between 1975 and 2000.

Even after the 1980 Refugee Act supposedly removed politics from the process and created a humanitarian basis for refugee admissions in line with the U.N. definition, the United States continued to accept mainly refugees from communist (or former communist) countries, mostly in Europe and Asia, along with Cuba. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) estimates that, for the 20-year period between 1983 (when they began keeping their own numbers) and 2003, “refugees from five countries…represented 77 percent of all arrivals: the former Soviet Union (25 percent), Vietnam (23 percent), Cuba (13 percent), the former Yugoslavia (9 percent), and Laos (6 percent).”

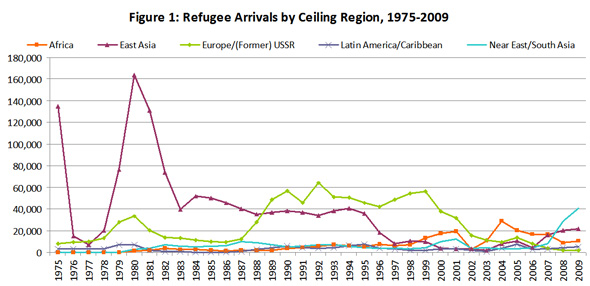

These flows are included below in the chart showing refugee arrivals from 1975 through 2009. The numbers are organized by “ceiling regions” used in the Presidential determination of the annual distribution of refugee admissions. The numbers do not include hundreds of thousands of Cubans, who actually arrived as “entrants” or parolees and then established their refugee status. These numbers also do not include the far smaller number of Haitians who entered as parolees. (The disparate treatment of Haitians and Cubans has long been the primary focus of claims of racism embedded in the refugee policy).

Source: Information for 1975-1989 taken from U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement, Annual Report 2002 (Cuba and Haiti not included in Latin America); information for 1989-2004 taken from Annual Flow Reports from DHS website; 2005-2009 numbers are taken from the PRM tables of “Arrivals Sorted by Region by Month” for FYs 2005-2010, available at wrapsnet.org.

The pattern of privileging European refugees is clear in the chart above, where European refugee flows persisted at high levels even after the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union, leading one legal scholar to claim that “no longer can communism serve as a proxy for racial selectivity.” From 1989 until 2003, Europe was once again the origin of the largest number of admitted refugees, as represented in Figure 2. In fact, for the five years from 1996-2000, and again in 2002, European refugees comprised more than half of all refugees arriving in the United States.

From 2004 through 2007, Africa was the ceiling region from which the largest number of refugees came. But, as can be seen in the chart, Africa’s ascendance occurred during a period of relatively few refugee arrivals, never reaching the levels of European or Asian refugee arrivals. Furthermore, Africans have had less access to the Priority 2 (P2) program which was designed to ease the entry of groups of “special humanitarian concern” to the United States. Unlike Priority 1 refugees, who are individually referred by UNHCR or U.S. embassies, P2s are members of specific (often religious or ethnic minority) groups identified by the State Department. P2s account for the majority of refugees and have what is referred to as “direct” access to apply for admission. Africans have generally not been identified as a special humanitarian concern.

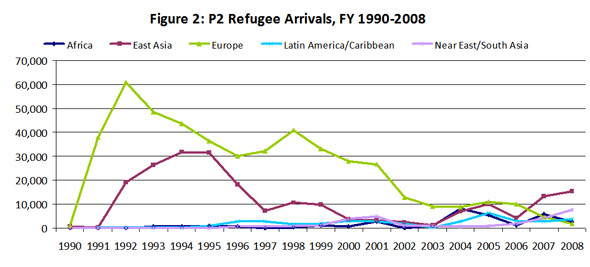

Historically, the P2 program was largely dedicated to Jews and Christians from the former Soviet Union, but it now includes religious minorities from Iran, Cuban political dissidents, Eritreans in the Shimelba Refugee Camp, and Iraqis employed by the U.S. government, their contractors, and the U.S. media. Once a group has been designated, the application process for P2s is quicker and family relationships do not have to be as clearly established since everyone from the group qualifies for an interview. Between 1990 and 2008, only 4% of P2 arrivals were from Africa, while 60% were from Europe, as seen in Figure 2.

Source: P2 numbers taken from PRM, Office of Admissions, “Arrivals by Case Priority, Fiscal Years 1990-2008, as of August 2008.” provided to researcher by PRM.

The Lautenberg amendment of 1990 (Public Law 101-167) “established a presumption of refugee eligibility for certain categories of persons from the Soviet Union and Southeast Asia,” as demonstrated in the admissions represented above. According to the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the refugee resettlement agency that deals with most former Soviet Union arrivals, the “special consideration” contemplated in the amendment amounts to a lower standard for determining refugee status. Even if a refugee applicant from the specified areas does not qualify for P2 status under the reduced criteria, the Lautenberg amendment (extended as the Specter amendment) provides them with an additional opportunity to come to the United States as a Public Interest Parolee (or PIP) under INA Section 212(d)(5). In 2010, the Lautenberg amendment was extended for its twentieth year, with parolees currently coming only from the former Soviet Union and a few former Soviet bloc countries.

Long after the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act, legal researchers continued to find that politics (both foreign relations and domestic lobbying) played a larger role than humanitarianism in the selection of P2 populations. One researcher noted in 2007 that humanitarianism seemed to be a more significant factor in the recent acceptance of large numbers of Lost Boys of Sudan and Somali Bantu under the P2 program. However, there has been a sharp decline in African admissions since 2007.

This decline does not reflect a decline in need. The humanitarian situation in many African refugee camps is dire. In February 2010, Doctors Without Borders complained of the continued lack of water, sanitation, land, and sufficient medical care in the Dadaab camps in Northeast Kenya, where over 260,000 refugees live in spaces built for a third of that number. The Dadaab camps, which were established nearly 20 years ago and house mostly Somali refugees, are the largest camps in the world. And yet, as these camps grew in 2009, U.S. arrivals from Africa dropped to a third of what they had been in 2004.

Arrivals have sunk partially as result of the fact that the P3 program was halted, but also because the United States has authorized fewer admissions from Africa. On October 8, 2010, President Obama released the refugee admission numbers for Fiscal Year (FY) 2011 in a memorandum to the Secretary of State. The ceiling for Africa is 15,000, which is slightly lower than in 2010. The 2011 ceiling is almost 25 percent lower than the average for the previous decade (2000-2010). It should be noted that African arrivals have generally fallen considerably below the ceilings, because of issues with processing, not need.

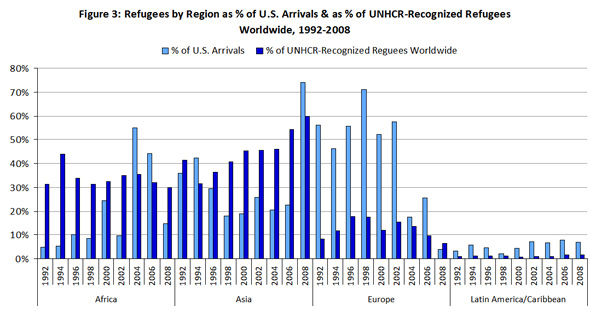

In fact, looking at U.S. refugee arrivals in the context of relative need—that is, the number of refugees in the world from any given region—underscores the under-representation of African refugees in U.S. admissions. Figure 3 below juxtaposes the percentage of arrivals to the United States from a given region out of all U.S. arrivals (lighter bar) with UNHCR-recognized refugees from that region as a percentage of the worldwide refugee population (darker bar). Where the lighter bar surpasses the darker bar, refugee arrivals to the United States over-represent that population in terms of worldwide need. Where the darker bar surpasses the lighter bar, those refugees are under-represented. In the last decade and a half, only European and Latin American and Caribbean arrivals (even without the Cuban entrants) are disproportionately high compared to the worldwide refugee population, with an average ratio of 3.3 times and 5 times respectively. Africa is the most under-represented continent, with 40% under-representation on average, even in the only period where there have been significant African arrivals. Asia is underrepresented at an average of 30%.

Source: US arrival numbers are taken from the Yearbooks of Immigration Statistics found at the Department of Homeland Security website: http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/yearbook.shtm. Numbers for UN-recognized refugees are taken from the UNHCR Statistical Yearbooks at UNHCR website: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/4a02afce6.html. For consistency sake the numbers have been adjusted so that Asian Former Soviet Union (FSU) countries are counted in Europe since until 1999 they were not listed separately but included in the Soviet Union for US data. Data from the US was arranged according to UN regions with the exception of the Asian FSU countries, which have been added to Europe for UN numbers as well so that the comparison is consistent. If these countries had been added to Asia instead (after 1999 when they were separated out), Europe would appear even more heavily overrepresented since Asian FSU countries make up a much smaller percent of US arrivals than they do UN-recognized refugees.

Just when it seemed that African refugees were finally getting some type of proportional treatment in the refugee program, the State Department suspended the P3 component, which accounted for a large portion of African entrants. P3 admissions have now been shut down for more than two years.

Testing DNA Testing: The DNA Pilot Project in Africa

The suspension of the P3 program followed years of discussion over the reliability and credibility of the program, which necessarily relied on attestation of relationships between family members. The pilot project that required applicants to provide DNA samples gave the State Department the opportunity to assess family relationships with potentially greater accuracy. High rates of refusal and negative results led to the suspension of the P3 program until more rigorous standards could be put into place. However, many critics of the testing believe the results did not necessarily reflect the level of fraud cited by the government.

It appears likely that DNA testing will become a major component of the P3 program in the future. DNA testing to prove family relationships has not previously been required in the refugee or the immigration context. There is a growing trend in which immigrants who are petitioning for family members voluntarily provide DNA samples when they have not been able to provide sufficient documentary proof of family relationships. This may be proactive on the immigrant’s part or suggested by the local USCIS office or consulate.

In the refugee context, there is more often a lack of documentation (birth and marriage certificates, adoption papers) to prove family relationships due to emergency departures and lack of stable functioning bureaucracies that would issue such documentation. In these cases, family relationships have previously been established through comparing testimony given by the anchor in the United States and the family members living in exile abroad. In addition, information given on the anchor’s initial refugee application and subsequent interviews and filings is checked against relationships claimed on the request for P3 processing of family members. DNA testing to prove such relationships is a new requirement.

The voluntary use of DNA in immigration cases was established in a memo from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)—which is now USCIS—to its field offices in 2000. It had previously been established that the INS could require blood parentage testing (through Blood Group Antigen or Human Leukocyte Antigen). However, the 2000 memo states that there is no “statutory or regulatory authority to require DNA testing.” In 2006, the USCIS Ombudsman recommended granting local offices the authority to require DNA testing in specific circumstances and launching a pilot program to require DNA testing in the immigration context. The USCIS Director at the time, Emilio Gonzalez, responded that the USCIS was trying to add a regulation allowing local offices to require DNA testing in specific situations when other evidence was insufficient or fraud was suspected, but not in all cases because the cost was prohibitive. Director Gonzalez did suggest that, when the industry had developed more, and DNA testing was broadly and affordably available, a blanket requirement might be a consideration. He ended the memo: “In the meantime, USCIS is considering conducting a pilot overseas, although a location has not yet been determined.” Apparent fraud in P3 refugee processing in East Africa provided the opportunity for such a pilot.

In February 2008, USCIS and PRM jointly began a pilot project in Nairobi, Kenya, to DNA test P3 refugee applicants. They began by asking refugees at their interviews (with no forewarning) to provide a DNA sample. The pilot project initially included 500 refugees. The pilot was testing relationships among people on the application; that is, the relationship of the primary applicant to his or her “derivative” relatives. The pilot did not generally test the relationship of the primary applicants to the anchor in the United States. Most applicants were Somali and Ethiopian.

PRM officials said they took this step because of reported fraud, especially in Nairobi. Reported fraud included not only what appeared to be mis-statements of relationships (more distant relatives being claimed as immediate relatives, for instance), but also the selling of refugee slots. There were widespread reports of the existence of brokers who sold slots, provided documents, and coached applicants for the interviews.

During the pilot, PRM found “high rates of fraud” for the 500 people from whom DNA was requested or collected. As a result, PRM expanded the program to Ethiopia, Uganda, Ghana, Guinea, Gambia, and Cote d’Ivoire. They attempted to test nearly 3,000 people in all; mostly from Somalia, Ethiopia, and Liberia. These three countries make up “the vast majority of P-3 cases.” According to the PRM fact sheet, quoted and misquoted widely in the press, PRM was “only able to confirm all claimed biological relationships in fewer than 20% of cases (family units). In the remaining cases, at least one negative result (fraudulent relationship) was identified, or the individuals refused to be tested.”

While it was widely reported that over 80% of cases were fraudulent, this figure includes all cases in which one or more family members did not show up to the interview, one or more family members refused the test (which was presented as voluntary), or the results indicated that one or more relationships were not what they were claimed to be. For example, if a case was comprised of five family members and DNA tests proved claimed relationships for only four, the whole case was considered fraudulent. A very large number of people either refused to take the test or did not show for it, and in the larger (3,000 person) sample this accounted for the “great majority” of negative cases, according to the State Department. A no-show (even one out of five people on an application) was interpreted as a fraudulent case without deducting even the normal rate of no-shows, which—while much smaller—was not insignificant. The government, however, will not release the underlying statistics. These statistics would indicate how many cases were no-shows or refusals, as well as the number of cases in which a single applicant within the family did not match and the number of cases in which multiple family members did not match.

In March 2008, the State Department stopped processing P3 applications in Kenya and Ethiopia. In May they halted the program in Uganda. On October 22, 2008, PRM stopped accepting Affidavits of Relationships (AORs) for all nationalities. An AOR is the form that the anchor relative in the United States files through a refugee resettlement agency in order to trigger a P3 case. For Africans, if the cases were approved by USCIS before March, they could go forward if everyone submitted to DNA testing. Refugees could proceed to the United States only where there was no biological relationship (spouses) or where every claimed relationship was proven through DNA testing. Families could not move forward if any claimed relative on the petition refused or failed to appear for the test. Anchors were generally not tested, since the government quickly decided that they did not yet have the legal authority to require the test of someone in the United States. The government moved forward with petitions that had been reviewed in the United States before March 2008 and sent on to the processing centers in Bangkok, Cairo, Havana, Ho Chi Minh City, Istanbul, Kathmandu, Moscow, and Vienna. Apparently, these did not require DNA testing.

What Constitutes Fraud in Refugee Admissions

Not only does it seem that the statistics on fraud may be exaggerated given that no-shows, refusals, and single negatives were all equated with entire cases being fraudulent, but there is also the question of what a negative test means. It seems that some instances of what the government is referring to as fraud stem, in fact, from cultural differences in the definition of family relationships. The U.S. government employs very strict definitions of immediate family built on biological relationships and the nuclear family (parents and children). However, in many African cultures the understanding of family is much more expansive. It is well documented that “fostering of children by non-parental kin is prevalent.” In some countries the tradition is that, if a parent dies, the father’s brother or mother’s sister substitutes as the parent. Children are taken in by grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other clan members in cases of death, divorce, needed care (for the child), or labor. “Another common feature of African kinship systems is classificatory kinship terminologies, according to which a large number of kin belong to a small number of categories.” Thus, the term “child” can be used to refer to nieces and nephews, “father” to refer to an uncle, and “mother” to refer to an aunt. In many African countries there is also a lack of legal adoption systems to formalize adoptive relationships, either for relative-adoptions or for children taken in by village or clan members as a result of conflicts in which many parents are killed.

While some refugees probably genuinely did not understand the difference between their parent/child relationship and the definition being used by the interviewers, it seems that many of them likely gave misinformation as a means of maintaining family unity. Employees of PRM and the JVA (Joint Voluntary Agency that conducts the initial interviews) stated that questions were asked—largely by Kenyan staff or through Kenyan interpreters—in such a way as to elicit specific information: “how many children did you give birth to” or “are born of your belly,” for example. However, the interview staff also stated that, while they would then note these relationships in the file, it was up to the individual USCIS officer to determine whether a particular child should be allowed to remain on the case, and that officers varied widely in the strictness of their interpretation of the law. A strict reading required that a child be legally adopted by the age of 16. A more informal interpretation is that the fostering parent must have taken in the child before leaving the country of origin for the relationship to be considered well established and legitimate. The refugee community certainly knew of negative determinations and many parents calculated the risk of revealing adoptive relationships. It should be noted that under the P1 and P2 programs, non-biological relationships can be dealt with by splitting the cases up into separate cases. However, P3 cases rely on these relationships for part of their claim to admission. Some refugee agencies warn that the term “fraud” is being overused to refer to not only the buying of slots, but also relationships that are not biological parent/child ties, but which nevertheless practically, physically, and emotionally function as legitimate and long-standing parent/child bonds.

The proposed AOR form contemplates the legitimacy of such relationships by including categories of foster children and foster parents. The AOR also states that, on a case-by-case basis, a person may be considered “in connection” with someone else’s application if, in the country of origin, they lived in the same household and were part of the same economic unit and if the individual “demonstrates exceptional and compelling humanitarian circumstances that justify his/her inclusion.” Even if such criteria are met, the person must establish his or her own persecution claim (unlike other derivatives). It could be quite difficult for a child to have understood enough of the trauma in his/her life to adequately explain and prove an individual claim of persecution. The form also clearly states that adopted relationship must be legally established before the age of 16.

Future of the P3 Program and DNA Testing

When the United States once again begins to allow relatives of refugees to enter the country through the P3 program, DNA testing will be required. All the details are not entirely clear at this point. PRM has revamped the AOR and the form will now be an official Department of State form, rather than an informal petition on the letterhead of each resettlement agency. The AOR will inform the anchor that DNA testing may be required to prove the relationship claimed on the form and that criminal prosecution can be initiated in the case of fraud. This “collection of new data” is currently being vetted through publication in the federal register, followed by a 60-day comment period, which began September 9, 2010. Testing would take place after the AOR is approved by the Refugee Processing Center in the United States and forwarded to the appropriate overseas processing entity, which will conduct a preliminary interview before requiring the DNA test. Comments on the new policy will be collected and reviewed, and could possibly affect implementation.

PRM plans to test biological relationships claimed between the anchor and their parents or children on the petition. It is not clear if the government will test the derivative relationships; that is, those between the primary applicant and his or her accompanying relatives. Derivative relationships are the purview of USCIS, which has not yet determined if and how they will use DNA testing. Derivative relationships were the only tested relationships in the pilot, including sibling relationships (which PRM decided to halt because the statistical confidence of the result is relatively low and so relationships cannot be definitively established). While fraud was suspected in both anchor to primary applicant and derivative relationships, only derivatives were tested in the pilot. However, the federal register notice states that the relationship between anchors and primary applicants will be subject to DNA tests under the new policy; the notice does not mention testing of the relationship between primary applicants and their derivative relatives. If USCIS wishes to do DNA tests for derivative relationships, it will require another round of testing and another period of delay.

The anchor will initially pay for the DNA tests. It is unclear if a final decision has been made as to whether the government will reimburse refugees for these costs. While the federal register notice states that the government may reimburse refugees, the proposed AOR states that they will reimburse costs if tests are positive and the case is approved. According to a government source, if reimbursement happens it may be made directly to the anchor or refugee or, more likely, through a reduction in the travel loan. The Department of State, through the International Organization for Migration (IOM), provides a travel loan for transportation of the relative refugees to the United States. The refugees repay the loan over time. Reducing the travel loan would affect the refugee resettlement agencies, which usually manage collection and receive a portion of the loans. In the pilot, the government paid for all testing.

According to a PRM official, there will most likely be a very strict policy on negative results and no-shows. A statement supporting the federal register notice announces, “If all claimed biological relationships are confirmed by DNA testing, PRM will present the case to DHS/USCIS for adjudication.” This wording implies that if even one relationship is invalidated by the test, the case will not move forward; although, PRM indicated that USCIS would make the final decision following a similar policy. In any case, it is unlikely that unsuccessful or absent relatives will be able to be dropped from the petition. The only exception to this zero-tolerance policy may be a case in which all children test positively to a mother but one does not test positively to the father, suggesting the possibility of rape or infidelity. Of course, this case should be technically covered anyway, since stepchildren are eligible for admission, but if relationships are not honestly claimed (for instance, stepchild or adopted child vs. biological child) they are likely to be denied.

A government official stated that if high rates of what they believe to be fraud reemerge when the P3 program is restarted, the program will end. DNA testing was described as “a last ditch attempt” to save the P3 program. There is also concern that there will be a huge increase in the number of adopted children and stepchildren claimed. This trend would be taken as an indication of fraud and could be cause for terminating the program.

Benefits and Concerns of DNA Testing

Interviews with six refugee settlement agencies and the UNHCR, as well as a review of the UNHCR note on DNA testing, have revealed the following benefits of and concerns with such testing:

BENEFITS:

- Evidence. DNA testing provides evidence for biological family relationships where no other evidence exists.

- Anti-fraud. DNA testing may cut down on instances of real fraud; that is, the buying and selling of refugee slots. Thus, it could sustain both public and government support for the program. It could also make the program a more manageable size and, therefore, PRM and USCIS would be more sympathetic to and efficient at processing legitimate cases.

- Anti-terrorism. DNA testing could prevent persons with ill-intent from entering the country through this particular channel.

CONCERNS:

- Discrimination. DNA testing must not be discriminatory, if it is used it should be applied equally across the world.

- Cost. The government bore the costs for the pilot, but it seems that refugees (or anchors) will have to pay the costs when the testing becomes a P3 requirement. UNHCR recommends that the government cover costs. If refugees were to pay for the tests, this could create a class-based system of refugee entries in which some refugees cannot afford to apply for their relatives.

- Delays. There is a concern that the DNA testing will create one or two very lengthy pauses in the process for a matter of months each. After pre-screening, a letter will go out instructing the anchor to have DNA testing by an approved lab; and also pay the lab to send DNA kits to the overseas refugee coordinator, who will then ask IOM to test the relatives on their next “circuit ride” that includes that location; the tests then go back to the lab; and finally the results are sent out. This process would be repeated a second time, later in the process, for the derivatives if USCIS decides to test them.

- Strict reading of results. Practitioners are concerned about what level of accuracy can be provided by DNA tests and how results will be used. There is a chance samples can be mixed up, for example. Also, there is a great likelihood that if one or more relationships is invalidated by the test, all relatives in the petition will be denied, despite the fact that others test positive. Petitioners should have the opportunity to explain any negative results; and confirmed relationships should be approved, barring flagrant and unexplained negative results.

- Family definitions. The use of DNA tests will further privilege biological nuclear family relationships over otherwise established parental/child relationships, defined as legitimate by the refugees’ culture. At the very least, refugees must be thoroughly informed of the difference in definitions of family and provided an opportunity to prove an informally adoptive or foster relationship and have that relationship recognized.

- Disruption to families. What if a child does not know that s/he is adopted? Or what happens if a woman was raped and has not revealed this to her husband (a common occurrence in some war-torn places)? The DNA test results in such cases could be devastating to the family. There was no counseling available during the pilot and there seem to be no plans to provide such a resource. UNHCR recommends that, at the very least, counselors need to be made available to refugees receiving the DNA results. Also, every measure should be taken to allow refugees to confidentially explain negative results, especially where the other tested relationships are positive.

- Privacy concerns. DNA collected for immigration purposes should not be used for any other purpose (i.e. added to a national database of DNA such as the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS). In the federal register and the supporting statement available from PRM, the government assures that they will never actually be in possession of the DNA, and that after entering positive or negative results sent by the lab that they will redact the report to contain no specific biological information.

Recommendations:

- Expand P1 and P2 admissions from Africa to fairly reflect the refugee crisis in this region.

- Seek alternative systems of tightening fraud controls; for example, strengthen the refugee registration system and make it uniform across refugee camps. UNHCR should be provided with resources to systematically document relationships and collect and store photographic and biometric identifiers during entrance registration and these should be rechecked and updated throughout the process. The main barrier to the effectiveness of this strategy is that the majority of P3 refugees do not live in camps where UNHCR is present. However, some may have previously lived in camps and been registered, so such registration could theoretically be drawn upon in these cases.

- Address the delays and inefficiencies in the I-730 process (Visa 92/93), whereby refugees (and asylees) can petition for their spouses and minor unmarried children in the first two years after gaining status without having to go through the refugee program. Because I-730s often takes longer than the P3 program, anchors are choosing to use the P3 process, thereby increasing wait times for refugees with no other alternative. Add parents as eligible beneficiaries of I-730 petitions in the INA.

- Develop a system for recognizing informal adoptive relationships, so that these relationships are not suspect and subject to the complete discretion of the individual USCIS officer. Do not require informally adopted or foster children with legitimate relationship to establish individual claims of persecution.

- Use of DNA should be limited to a last resort when documentary evidence is unavailable and testimony given by the two sides appears unreliable. In such specific cases of suspected fraud, DNA testing should be a voluntary option applicants can avail themselves of to prove relationships.

- Claims based on proven relationships (by documentation, testimony, DNA, or otherwise) should be approved. If an applicant or derivative beneficiary has failed to prove his or her claimed relationship or failed to appear, that should not be cause to deny everyone on the application.

- If DNA is required, testing should follow the guidelines set forth by UNHCR in their note on the subject, including the government bearing the cost, respecting privacy, and providing counseling. DNA testing should not be used as the only definitive indicator of relationships, without an opportunity for relationships to be explained and legitimate relationships in the case to be approved.

- Maintain the integrity of the process by providing all relevant data to individuals monitoring the program.

Many of these recommendations are likely to be voiced by groups responding to the proposed rule changes during the current public comment period. The Department of State’s response to such concerns and its handling of the many issues raised by DNA testing will likely have a significant effect on whether the P3 program remains a genuine lifeline for African and other vulnerable refugee populations.

Published On: Thu, Oct 21, 2010 | Download File